Skip list intuition

The AVL tree is used all over the place in modern routing software. Link-state databases, forwarding/routing information bases and so on all use this data structure as a way to search/insert/delete information in logarithmic time. The thing is, this data structure was invented in 1962. The red-black tree was invented in 1972, so it not all that new either. I was curious as to what has cropped up in the literature more recently in this area of computer science. A couple data structures came out of that investigation, but the one I like the most is the skip list. Let me give you a brief overview of the intuition behind it. For implementations see here (Python) and here (C). Its super cool because it takes the basic idea of a linked list, then introduces a tiny bit of randomness to improve the search/insert/delete time from linear to logarithmic.

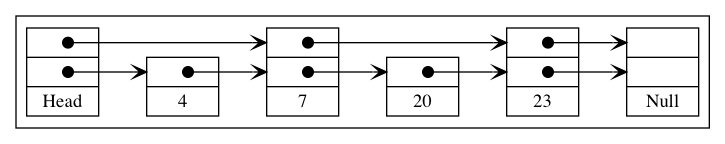

A good place to start is to think about what would happen to a sorted linked list if you put an extra pointer at every other node, so you would have one pointing to the next node and one which skips a node and points to the one after:

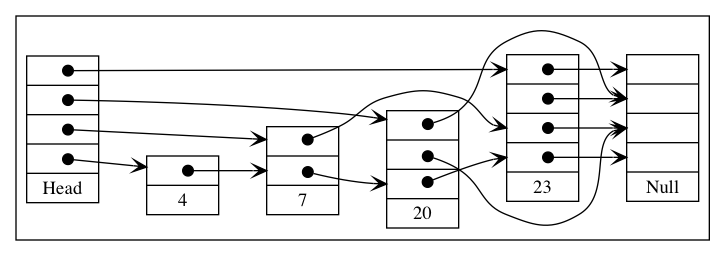

Now we have two lists, one of which is half the size. If the element we were searching for happens to be in the smaller list and we happen to be iterating through that one, then it will be found in O(n/2). Continuing this idea with three pointers, where the third one skips 2 nodes at a time, we would get three lists and again if our element was in the smallest list it could be found in O(n/3). If we had n pointers, the nth list would point directly to the last element, meaning that if you were looking for that element and used the nth list it could be found in O(1) time:

Intuitively you can see that some number of lists between 1 and n would give you search times somewhere in-between constant time and linear time, depending on which element you were looking for. We wouldn’t want to use n lists, because then the search time devolves into linear time because we now have a linear number of lists to check. You can see this by noticing that each additional list after n/2 lists will only have one element because the 2nd bound in each of them will jump over all the remaining of the elements.

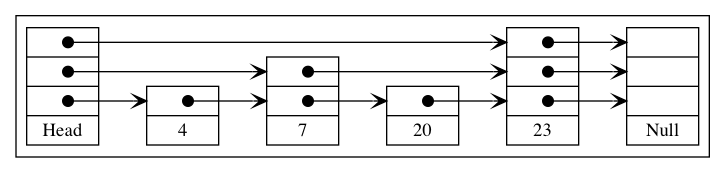

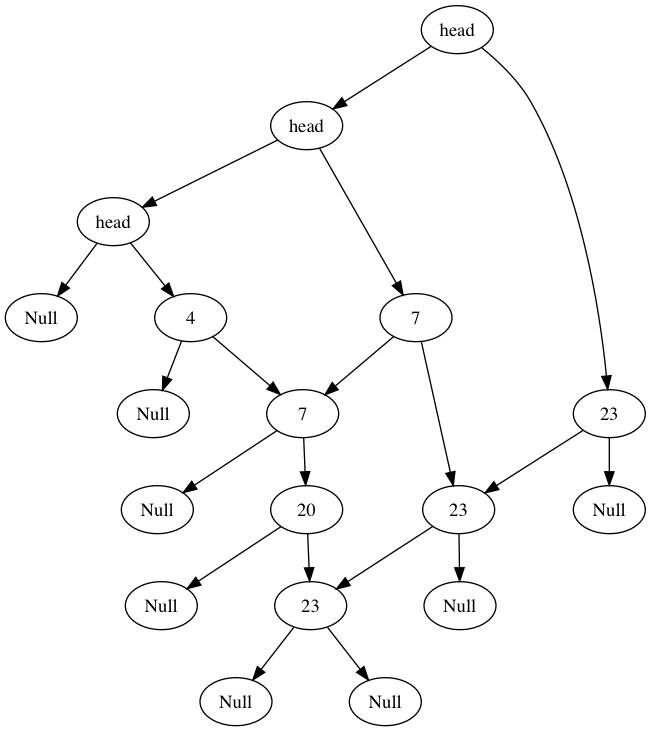

A better idea is to have each additional list skip every other node in the list immediately below it. In that case, the 3rd list actually has n/4 elements, the 4th would have n/8 and in general for list i there would be n/(2^i) elements:

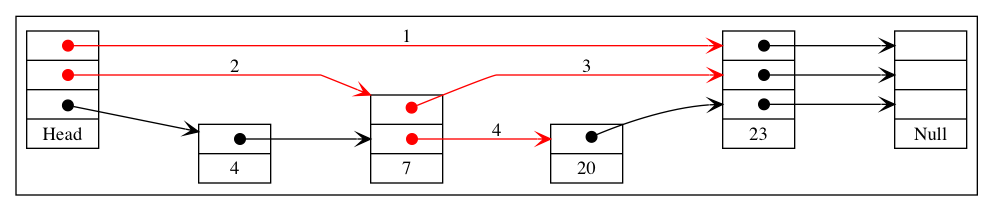

Instead of every other node, you could do every kth node, which would just change the formula to n/(k^i) for the list i. Regardless of the choice of k, we now have logarithmically decreasing number of elements in each additional list. Considering each pointer as a node in a separate list, the total number of “nodes” (for k = 2) is n + n/2 + n/4 + n/8 … + 1 which varies depending on if n is a power of 2 or not, but it is bound from above by 2n. So we basically doubled the number of logical nodes, but in exchange we get what is really a binary search tree in disguise. To see this, it helps to understand how a skip list is walked. To insert the value 10 the following procedure would be used:

- Start at the top list move to the right, 10 < 23 so drop down a list

- Move to the right, 10 > 7, so move to the right again

- 10 < 23, so drop down a list

- 10 < 23 and we can no longer drop down a list, insertion point found

The rules should be clear: move as far right as you can while your element is larger then the current element, if you hit an element larger or the end of a list then drop down. If you cannot drop down the algorithm terminates. The key thing to note is that this right or down traversing is the exact same as a left or right traversing in a binary search tree, so from the perspective of the iterator the skip list appears as:

Every time we go right or down in the skip list, a whole subtree gets removed from our set candidates. This is why the time complexity of search/insert/delete becomes logarithmic. If we could maintain this balanced structure then everything would be fine. The problem is that if I were to do my inserts and deletes in plain old BST-style, then we run into the same problem that exists with BSTs - it could become very unbalanced and then the performance would degrade to linear time. Consider deleting 4, 7 and 20 then inserting 3 elements greater than 23. If we didn’t add any extra pointers for those inserts, they would all be part of the top list making it a normal linked list with linear operations. Recall our end goal is to have n/(k^i) nodes in level i. If we set the probability of a given node having i pointers to 1/(k^i), then for level i, the total is 1/(k^i) + 1/(k^i) … = n / (k^i) which is exactly what we want! If k=2, then you can think of it like flipping a coin where the number of consecutive of heads (or tails) you get is the number of pointers you include as part of the insert operation.